MYPLACE team members Dustin Gilbreath, CRRC, Georgia on history and Saakashvilli’s “rehabilitation” of Telavi, in Georgia, site of MYPLACE fieldwork.

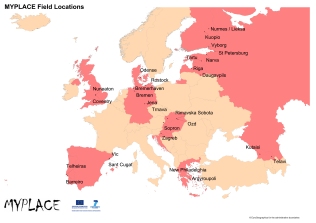

For more information on the MYPLACE project visit the project’s website: HERE

All the MYPLACE WP2 reports, as referred to in the text, can be found HERE

Claims to 2000 or even 3000 years of nationhood are not difficult to find in Georgia as has been amply documented (see Pelkmans 2006, Suny 1994, Rayfield 2013). The former president Mikheil Saakashvili was even fond of using the earliest human skulls found outside of Africa, in Dmansi in Southern Georgia, as proof that Georgians were “ancient Europeans.” The pride in Georgia over ancient aspects of history is palpable. Yet, the events of more recent Georgian history often have pain and trauma attached to them. In this historical context, the CRRC-Georgia conducted focus groups, semi-structured interviews, and observation in Telavi, focusing on YMCA Telavi’s work with IDP youth. Research data was gathered as a part of a European Union funded project, MYPLACE. Fieldwork in Telavi was conducted in order to better understand the role of historical memory in the civic engagement of young people (aged 16 to 25), and the inter-generational transition of memory in both IDP and non-IDP families.

Beginning shortly before and stopping shortly after the end of fieldwork, the historic city center of Telavi was being ‘rehabilitated’ by the government. Discussion of the rehabilitation with respondents proved an interesting lens on how history effects and produces affect in the everyday lives of young people in Telavi. Furthermore, the rehabilitation can be seen as a metonym for the government’s larger efforts at rehabilitating many sites in the country, and more importantly how these ‘rehabilitation’ and ‘development’ projects shaped citizens’ relationships with the state through the use of history and its relation to time.

As mentioned above, Georgia’s ancient history is often glorified in both every day and political discourses. The palace of King Erekle II, a celebrated 18th century king of Eastern Georgia, is located in Telavi’s historic center. The historic center with King Erekle’s palace had functioned as a site of memory, which elicited memories of the glorious past. The process of rehabilitation, however, began not only to evoke memory of the glorious past, but also to serve as a reminder of the rule of the Mikheil Saakashvili and the United National Movement (UNM), which were responsible for initiating the rehabilitation project in Telavi.

Participants in the MYPLACE project’s research in Telavi unanimously agreed on three things in regards to the ’rehabilitation’ of the city: the quality of works and materials used in rehabilitation were sub-standard; historical monuments were not well preserved; coordination with the local population was less than adequate. These complaints in many ways illuminate the political situation at the time of fieldwork and do so as if a light containing the political problems of the day were being projected through a prism, with the complaints emitted as rays.

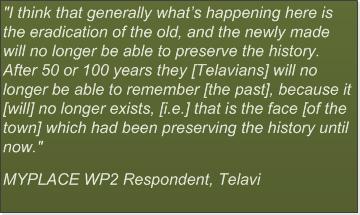

The fact that, in the eyes of informants, the quality of works and materials used in rehabilitation was less than standard and the fact that the historical monuments were not well preserved points to the felt defamation of memories of the glorious past. One should remember that the sites being rehabilitated had previously evoked affects of pride in the celebrated and memorialized glorious past and served as sites of memory for this past. As one respondent stated:

“I think that generally what’s happening here is the eradication of the old, and the newly made will no longer be able to preserve the history. After 50 or 100 years they [Telavians] will no longer be able to remember [the past], because it [will] no longer exists, [i.e.] that is the face [of the town] which had been preserving the history until now.”

With the perceived (and actual) debasement in quality in rehabilitating the sites, the government had effectively defamed the past which they had previously tried so hard to be symbolically associated with.

This symbolic association took a variety of forms of meddling with the past, but one notable example comes from former-President Mikheil Saakashvili’s first presidential inauguration in 2004. Saakashvili, before his official inauguration came to Gelati Cathedral in the Imereti region in order to take an oath on the grave of 11th-12th century Georgian King, David the Builder. King David is accredited with the inauguration of the Georgian ‘golden age’ of the 11th-13th centuries and is known, as his name implies, for the geographic expansion and architectural development of the country. The intended symbolism that Saakashvili’s action was supposed to project was clear. Despite this symbolic gesture, complaints about construction quality, not only in Telavi but elsewhere in the country, imply that maybe Misha, as he was commonly known, will not be remembered for what he helped to build.

Moreover, the complaints of the population of Telavi regarding rehabilitation works in the town point to another inadequacy in the country at the time – an apparent lack of democracy. After 2007, the government had been sliding towards authoritarian rule (Slade and Tangiashvili 2013). Telavi respondents, in mentioning which events were important in recent history mentioned the “terror tactics” of former President Saakashvili’s party, the United National Movement (UNM), in 2007-2012. In complaining that the government had not adequately consulted with the local population about the rehabilitation works, in microcosm, a country wide issue was on display in fieldwork discussions.

Further enunciating the democratic deficit, consultations with the local population in almost all respects were non-existent. Adding to the dismay, no contracts were signed with residents whose homes were being ’rehabilitated’ regarding when works would be finished or whether the structural integrity of homes would be taken care of. After the end of ’rehabilitation’ works, families often came home to devastated interiors, destroyed furniture, and structurally questionable domiciles.

Window frame inside of a home in Telavi center after rehabilitation of building façade. Photo by Tinatin Zurabishvili

In looking at these larger issues in microcosm, the past was obviously present in relation to the ‘rehabilitation’ of historic sites, but at the same time, the future was also being meddled in.

Ongoing construction works in and of themselves can inherently be seen as a projection into the future – a building being built today may be in response to the needs of the day but they are also for a projected future use. In looking at construction as a projection into the future, coming along with it comes a projection of what that future will be like. Thomas De Waal, in a pamphlet published by the Carnegie Foundation, characterized the rhetoric of the UNM as speaking in the “future perfect” (De Waal, 2011). Speaking in the future perfect meant that the government made statements about what the country would be and would have. The government not only projected into the future through its rhetoric, but also through construction. Construction was further accompanied by glossy brochures which were widely distributed with computer generated images of what finished buildings would be like. Works in progress were not left to the imagination alone, but an actual image was delivered along with the grounds broken for construction.

In Telavi, as it was elsewhere in Georgia, the projected future muddied memories of the glorious past. One young woman who was interviewed during MYPLACE fieldwork stated that she tried not to look at what was happening in the historic center and tried not to notice what was new while walking through it. Her desire not to know is at least twofold in its avoidance. In not looking around it seems reasonable to say this informant was avoiding both the defamation of the old as was shown previously to be felt, but also the creeping reminder of the present ’terror’ and the then present government’s projected vision of the future. Sites of memory had been transformed into sites of reminder.

This future though was not to last. During fieldwork a viable opposition led and financially backed by Georgian billionaire, Bidzina Ivanishvili emerged. Its emergence and eventual victory in parliamentary elections ruptured the future that had been projected. With the loss of positions of authority as well as moral authority, the UNM had lost its ability to project the future it saw on Georgia – their future had become part of the past. ’Rehabilitation’ works along with a number of other projects in the country were halted shortly after Ivanishvili’s Georgian Dream came to office. The halting of works in some way has preserved the sites of memory in the historic center of Telavi; their preservation though is not the kind which a preservationist would hope for, but rather, the preservation of the alteration of the sites. This preservation has thus, in turn, made sites of memory in Telavi polysemous. In preserving the alteration of the sites, now for those in Telavi, the sites are linked to both the distant past and the less than democratic recent past.

For how long the ‘rehabilitated’ buildings will serve as sites of memory of the recent past is unclear, but what is clear is present and future governments in Georgia will continue to meddle in the past and project their visions into the future thus impacting Georgians, young and old alike.